English Builders History From 1700 to Today & Their Work

For over three centuries, England’s landscape has been shaped by builders. These are the people and firms who take plans and turn them into real houses, bridges, and cities. Their work is not just about bricks and mortar. It reflects the changing needs of society, new laws, and advances in technology. Knowing their stories helps us understand the buildings we live in, work in, and pass by every day.

We will take a look at how builders from 1700 to today show how the craft evolved from a local trade into a major national industry.

Main Points to Know:

- Builders before the 1800s were usually master craftsmen who worked directly on a project, managing small teams.

- The Industrial Revolution created a huge demand for new housing and infrastructure, leading to the rise of large speculative building firms.

- The 20th century introduced new materials, like reinforced concrete, and new regulations that changed how builders worked.

- Today, the role splits into large national companies for major projects and smaller, specialist firms for renovations and bespoke homes.

- A builder’s success has always depended on practical skill, financial management, and adapting to new rules and materials.

What a Builder Does & Why It Changed

A builder’s job is to construct or repair physical structures. For most of history, this meant organising labour, sourcing materials, and ensuring the work was done correctly. The title “builder” could mean different things in different eras. This change in role is the key to understanding their history.

In 1700, England was largely rural. Construction was local. A “builder” was often a master bricklayer or carpenter. He would employ a few journeymen and apprentices. They worked on one project at a time, like a manor house, a church, or a farm building. Materials came from nearby: timber from local woods, brick from local clay, stone from local quarries. The builder was a hands-on craftsman, and the site manager rolled into one.

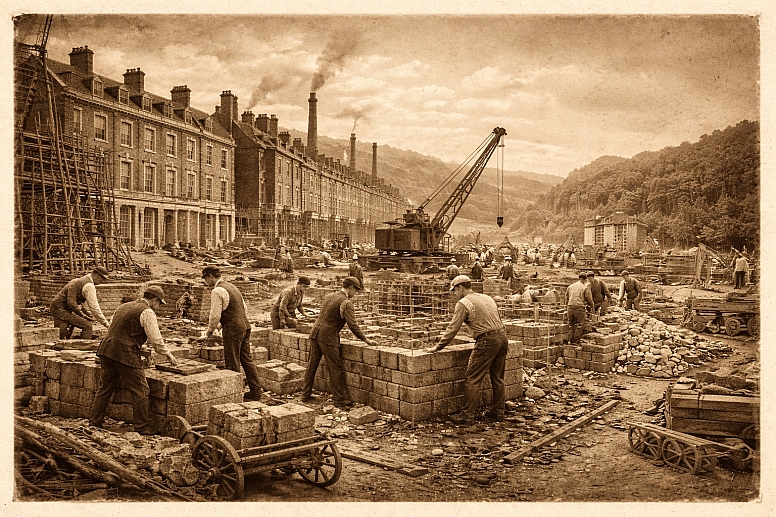

The population grew rapidly in the late 18th and 19th centuries, especially in towns and cities. The Industrial Revolution meant people moved to find factory work. They needed houses, fast. This demand created the “speculative builder.” This builder bought a plot of land, built rows of houses on it, and then sold them for a profit. He didn’t work for a single client; he built for an unknown future buyer. This was a huge shift. It turned construction and building from a craft service into a financial enterprise. Builders now needed capital to buy land and materials before seeing any return. They had to manage much larger gangs of labourers, often subcontracting specialised tasks.

The 20th century brought more changes. After the world wars, there was a massive need to rebuild and provide “homes for heroes.” The government became deeply involved, commissioning huge estates of public housing. Builders had to work to strict government standards and cost limits. New materials like pre-stressed concrete and steel frames became common, requiring new skills. Later, regulations focused on energy efficiency, safety, and access. Today, a builder must be an expert in compliance as much as in construction.

Throughout all this, the builder’s core mission remains: to assemble skilled people and reliable materials to create a sound, useful structure. How they achieve that mission has been transformed by economics, technology, and society.

The Builder’s Evolving Toolkit

A builder’s work is defined by three pillars: the materials they use, the labour they organise, and the business model they operate under. These are the underlying mechanics of the trade.

Materials and Methods

- 1700s-early 1800s: Construction was load-bearing masonry. Thick brick or stone walls held up the floors and roof. Foundations were shallow. Joists were timber, cut by hand. Roofs were framed with timber and covered with slate or tile. Windows were small-paned due to the cost and difficulty of making large sheets of glass.

- Mid-1800s onward: Mass-produced materials arrived. Machine-made bricks were uniform. Cast iron, and later wrought iron, allowed for larger interior spaces in factories and railway stations. The arrival of cheap plate glass meant larger windows. Portland cement, patented in 1824, eventually led to widespread concrete use.

- 20th Century: Reinforced concrete changed everything. It allowed for taller buildings and longer spans. Steel frames became the skeleton for skyscrapers. Prefabrication emerged—sections of buildings were made in factories and assembled on-site, speeding up construction for post-war housing.

- Late 20th Century to current day: A focus on performance drove new materials. Cavity wall insulation, double-glazed units, and modern damp-proof membranes became standard. Sustainable materials like engineered timber (e.g., glulam) and recycled aggregates are now common. Digital fabrication, like cutting roof timbers by computer, allows for extreme precision.

Labour and Organisation

- The Master Builder Model: The builder was the lead craftsman. He hired a small, permanent team he knew well. He often trained apprentices himself. The pace was set by the skill of the workers.

- The Contractor Model: As projects got bigger, the builder became a general contractor. He won a contract based on a price and schedule. He then hired specialist subcontractors for plumbing, plastering, electrical work, etc. The builder’s job shifted from direct work to coordination, scheduling, and quality control over these subcontractors.

- The Modern Site: Today, a large building site is a web of different firms managed by a main contractor. Strict safety rules (like the CDM regulations) govern everyone. Labour is often hired on a project-by-project basis. The builder’s management skill is as critical as their trade knowledge.

Business and Finance

- Craft-Based: Early builders were paid by their client, often a wealthy landowner, as the work progressed.

- Speculative Building: This required upfront investment. Builders borrowed money, built houses, and hoped to sell them quickly to repay the loan and make a profit. This was risky but could be very lucrative.

- Fixed-Price Contracts: The standard for most of the 20th and 21st centuries. The builder agrees to do the work for a set price. Any cost overruns come from their profit. This requires accurate estimating and tight cost control.

- Design and Build: A modern trend where a single company (the builder) takes responsibility for both designing and constructing a project. This can streamline the process but places more risk and coordination burden on the builder.

The transition from craftsman to contractor to corporate manager is the technical story of the British builder. Each stage required a new set of non-physical skills: estimating, contracting, scheduling, and financial management.

Builders in Different Eras & Roles

The Georgian Master Builder (c. 1720-1780)

- Specific Constraints: Transport was slow and expensive. Almost all materials had to be sourced within a few miles. Designs were often from pattern books, not architects. Labour was manual and slow.

- Common Mistakes: Underestimating the quantity of local materials (like good-quality stone). Poor seasoning of timber, leading to warping later. Inaccurate setting out of classical proportions, which would be visibly obvious.

- Practical Selection Advice: A successful Georgian builder was deeply integrated into his local area. He knew which clay pits made the best bricks and which quarries had the most workable stone. He maintained a loyal team of skilled men. If you were hiring a builder in this era, you would look for a man with a proven record of completed local houses and good relationships with the gentry or church commissioners. His reputation was his entire livelihood.

The Victorian Speculative Builder (c. 1850-1900)

- Specific Constraints: Working on tight profit margins. They needed to build rows of houses quickly and cheaply to meet demand. Dealing with new, and sometimes unreliable, mass-produced materials like cheap slate or poor-grade iron.

- Common Mistakes: Cutting corners on foundations or drainage to save money, leading to subsidence or damp problems that persist today. Using unskilled, low-paid labour for critical tasks results in poor workmanship. Over-extending financially by starting too many plots at once.

- Practical Selection Advice: The most successful speculative builders, like Thomas Cubitt, operated at scale with better quality control. They invested in their own workshops and employed direct labour. For a homebuyer in 1880, a house built by a known, larger firm was often a safer bet than one from a small, fly-by-night operator. You would look for solid brickwork, proper window reveals, and evidence of a damp-proof course (a late-century innovation).

The Post-War Municipal Contractor (c. 1945-1970)

- Specific Constraints: Building vast numbers of homes to strict government cost guidelines (“cost yardsticks”). Using new, sometimes untested, prefabricated systems. Often working on difficult, cleared bomb-site land.

- Common Mistakes: Rushing the construction of large concrete panel systems, leading to poor sealing and later weatherproofing failures (a major cause of problems in later decades). Prioritising speed and cost over communal space or aesthetic detail, creating bleak environments. Inadequate understanding of new materials, like high-alumina cement, which failed catastrophically in some cases.

- Practical Selection Advice: The government was the client, so selection was by tender. The winning builder was often the one who could promise the fastest completion at the lowest cost. Quality suffered as a result. This era shows that the builder’s client and their priorities (government cost-cutting) directly shape the long-term outcome, sometimes negatively.

The 1980s Private Estate Developer

- Specific Constraints: Creating attractive, marketable homes for a rising home-owning society. Complying with newer building regulations on insulation and energy. Building on greenfield sites at the edge of towns.

- Common Mistakes: Creating identikit estates with little character or community focus. Using standardised designs that didn’t always suit the site, leading to drainage issues. Applying decorative features (like fake timber beams) poorly.

- Practical Selection Advice: Large national firms like Barratt and Wimpey dominated. They offered “package deal” homes. For a buyer, the warranty (the NHBC Buildmark warranty became standard in the 1980s) was a critical new protection. You were no longer just buying from a builder; you were buying a product with a guarantee, which shifted some risk away from the consumer.

The Contemporary Specialist Renovator (2000-Current Day)

- Specific Constraints: Working on existing, often listed or period buildings with unpredictable problems. Navigating complex planning permissions and conservation area consents. Integrating modern services (wiring, plumbing, insulation) into old fabric without damaging its character.

- Common Mistakes: Using modern cement-based mortars on old soft brickwork, trapping moisture and causing spalling. Installing inappropriate double glazing in historic windows destroyed their appearance. Adding insulation without considering ventilation led to condensation and rot.

- Practical Selection Advice: This is a specialist field. A good renovation builder understands historic building physics. They use lime mortars, traditional breathable paints, and sympathetic repair techniques. They work closely with architects and conservation officers. You would select them based on a portfolio of specific, high-quality restoration projects, not on their ability to build a new house quickly. Membership in bodies like the Federation of Master Builders (FMB) or specialist heritage guilds is a good sign.

Comparative Evaluation: Master Builder vs. Modern Main Contractor

We can understand the trade’s evolution by comparing the archetype of a 1750 master builder with a modern-day main contractor running a multi-million-pound project.

| Criteria | The Master Builder (c. 1750) | The Modern Main Contractor (c. 2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Hands-on master craftsman and site foreman. | Corporate manager, coordinator, and risk-bearer. |

| Scale of Work | One project at a time, locally. | Multiple, simultaneous projects across regions. |

| Materials | Local, natural materials (stone, timber, lime). | Global supply chain (concrete, steel, composites, specialist products). |

| Labour | Small, permanent team of known craftsmen. | Large, temporary workforce of employed staff and dozens of subcontractor firms. |

| Design Input | Often interpreted plans from pattern books; significant on-site discretion. | Works from detailed architect and engineer drawings; minimal deviation allowed. |

| Client | A single, known individual (landowner, institution). | Could be a private developer, a corporation, or a government body. |

| Key Skills | Supreme craft skill in a trade, ability to train men, and personal reputation. | Financial management, legal contract knowledge, digital scheduling (BIM), and health & safety law. |

| Risk | Risk to personal reputation for poor work. | Massive financial and legal risk from delays, cost overruns, or site accidents. |

| Output | A unique, craft-focused building like a country house. | A standardised, regulation-compliant building like an office block or housing estate. |

The master builder’s authority came from his skill. The modern contractor’s authority comes from their systems. The former was an artist-manager; the latter is the CEO of a temporary production line. Both are valid models for their time, but they require completely different mindsets and skills.

Expert-Level Considerations

Experienced builders and construction historians think about factors that go beyond the basics of getting a building up. Here are some nuanced points.

The Importance of “Soft” Land Costs: Beginners focus on construction costs. Experts know that a project’s viability often hinges on land cost and “abnormals.” An abnormal is an unexpected ground condition or site cost. A cheap plot of land might be an old landfill site, requiring massively expensive foundation work. A builder in 1820 or 2025 must have the skill (or hire a good surveyor) to assess ground conditions before committing. The most famous builders were often shrewd land buyers first.

Supply Chain Dependency: A modern builder doesn’t control their materials. They rely on a chain of suppliers. A delay in window deliveries from Europe or a shortage of roof tiles can stop an entire project. Expert builders mitigate this by ordering materials very early, having backup suppliers, and building buffer time into schedules. In the 18th century, a bad harvest could delay the production of oak for beams. The fundamental problem of supply is ancient.

The Tyranny of the Programme: On a complex site, every trade depends on another. The electrician can’t start until the plasterer has finished, but the plasterer needs the plumber to set the pipes first. A detailed construction programme is the bible. An expert builder doesn’t just have a schedule; they constantly monitor it, identify the “critical path” of interdependent tasks, and solve delays before they cascade. This logistical skill separates adequate builders from exceptional ones.

Regulation as a Design Force: Building Regulations aren’t just a checklist; they actively shape design and method. Part L regulations demand high levels of insulation. This means wall thicknesses, window specifications, and ventilation systems are all dictated by law. An expert builder understands these regulations so well that they can advise the design team early on, suggesting cost-effective ways to comply. They build the rulebook into their planning from day one.

The Legacy of Reputation: For a small or specialist builder, reputation is everything. But it’s not just about being known. It’s about the type of reputation. The best builders cultivate a reputation for solving problems, not causing them. When an architect or homeowner has a tricky, unexpected issue—a rotten beam found during renovations, a planning officer’s odd request—they call the builder known for calm, smart solutions. This reputation for problem-solving is more valuable than any advertisement.

Failure Modes & Misconceptions

Things go wrong when the realities of building are misunderstood or ignored.

Misconception: The Lowest Quote is the Best Choice. This is the most common and costly error. A very low quote often means the builder has made a mistake, missed something, or plans to use poor materials or labour. They may then demand more money later (“extras”) or cut corners. A realistic quote reflects the true cost of quality materials, skilled labour, and a reasonable profit.

Failure Mode: Poor Communication and Unclear Contracts. A building project is a web of decisions. Failure happens when changes aren’t written down. A client asks for a different tile; the builder agrees verbally. Later, the client is shocked by the extra cost, or the builder absorbs the loss. A written variation order for every change, no matter how small, is essential. Most disputes stem from undocumented assumptions.

Misconception: Old Buildings Were Built Better. They were often built with better materials (slow-grown oak, lime mortar) but not necessarily better methods. Damp-proof courses were rare, insulation was nonexistent, and services were primitive. Many old buildings have settled, rotted, or been altered badly over time. A “solid” old house may need massive, expensive repair. Modern buildings, when built to regulation, are warmer, drier, and safer.

Failure Mode: Ignoring the Sequence of Work. Trying to paint before the plaster is dry. Laying a floor before the walls are sealed. Installing a kitchen before the floor screed is poured. These errors cause rework, damage, and delay. They happen when a builder rushes or a client pressures for the next visible step without understanding the necessary curing or drying times.

Misconception: A Builder is Just a Project Manager. On large sites, the builder is a manager. But on smaller projects, the best builders still have deep hands-on trade knowledge. This lets them spot when a subcontractor’s work is substandard, understand how different materials interact, and propose practical fixes. A pure manager without craft experience can be disconnected from the physical reality of the site.

How to Think About Builders & Building

Whether you’re studying history or planning a project, use this framework to analyse any building situation.

-

Identify the Primary Driver. What is the main force behind this project? Is it speculative profit (Victorian terraces, modern estates), urgent need (post-war housing), personal expression (a Georgian mansion, a contemporary custom home), or legal/regulatory requirement (a factory upgrade for safety)? The driver determines the priorities: speed, cost, quality, or compliance.

-

Analyse the Constraints. Every project operates within limits. List them:

- Financial: What is the budget? How is funding secured?

- Material: What is available locally or through supply chains? What do regulations allow or forbid?

- Labour: What skills are available? Is it unionised, subcontracted, or direct?

- Regulatory: What are the planning laws, building codes, and safety rules?

- Site: What are the ground conditions, access, and surrounding context?

-

Determine the Builder’s Role. Is the builder the creator/entrepreneur (speculative builder), the client’s agent (traditional contractor), or the integrated provider (design-and-build firm)? This tells you where their interests lie and what risks they hold.

-

Evaluate the Outcome Against the Context. Don’t judge a 1960s concrete tower block by 2025 standards of aesthetics and insulation. Judge it by the standards of its own time: did it provide safe, dry homes quickly and within the cost yardstick? Did the builder execute the prevailing design correctly with the materials and knowledge available then?

-

Apply to Your Own Project. If you are hiring a builder today:

- Define your Driver (Is it adding value, creating a dream home, or essential repair?).

- Know your Constraints (budget, timeline, listed building status).

- Choose a Builder’s Role that fits (a large firm for an extension, a niche renovator for a period cottage).

- Get detailed, written quotes and a clear contract.

- Check their past work and speak to previous clients.

- Remember that good communication and documented changes are as important as the initial price.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was the most important English builder? It depends on the definition. For transforming the business of building, Thomas Cubitt (1788-1855) is pivotal. He industrialised the process, employing thousands directly, with his own workshops and supply chains. He built large parts of London’s Belgravia and Pimlico. For iconic projects, Sir Robert McAlpine (“Concrete Bob”) and his firm built major 20th-century landmarks like the Millennium Dome.

What is the difference between a builder and an architect? An architect designs the building. A builder constructs it. Historically, before the 1800s, this line was blurry; the master builder often designed as he built. Today, they are separate, regulated professions, though some firms offer both services (design and build).

Why are so many old builders’ firms still around today? Firms like Wates (founded 1897), Willmott Dixon (1852), and Kier (1920s) survived by adapting. They moved from general building into specialised contracting, services, and public-private partnerships. Their longevity is due to strong management, financial caution, and evolving their services with the times.

What is a “speculative builder”? A builder who constructs buildings (usually houses) without a specific buyer in place, hoping to sell them for a profit upon completion. They speculate on the future market. This model drove most of England’s suburban expansion from the 1800s onwards.

How do I find a good builder for a small home renovation? Look for specialists in your type of project (e.g., Victorian renovations). Get multiple detailed quotes. Ask for references and go see their completed work. Check for membership in a reputable trade association like the Federation of Master Builders (FMB), which offers a warranty scheme. Ensure they provide a clear, written contract.

What is the biggest challenge for builders today? A combination of skilled labour shortages, volatile material costs, and incredibly complex regulations around sustainability (like the Future Homes Standard). Balancing the demand for speed and cost with the need for high-quality, energy-efficient, and safe construction is the central challenge.

If this history has made you think about a building project, start by looking at buildings you admire from your preferred era. Notice the details in the brickwork, the roof lines, and the window proportions. Then, research local builders who have worked on similar properties. Your first and most important step is to have a clear, written list of what you want to achieve before you speak to a single professional.