Russian & Eastern European Builders and Architects: From Soviet Monuments to Modern Giants

The construction and architectural history of Russia and Eastern Europe is defined by the centrality of power. More than in most regions, building here has been a function of ideology, territorial ambition, and state capacity. Architects and builders did not merely respond to markets or private clients; they operated as extensions of political systems, tasked with materialising visions at a continental scale.

The Construction and Architectural History of Russia and Eastern Europe: Power, Politics, and Vision

From the monumental works of the Tsars and the industrial behemoths of the Soviet era to post-Soviet oligarchic conglomerates and globally circulating architectural imagery, the region reveals a sharp division between those who design and those who execute—a split institutionalised under socialism and never fully repaired.

This profile examines both sides of that equation:

- the entities and systems that built the region

- and the architects who shaped, challenged, or symbolised those systems across eras

Historical Foundations: Imperial and Soviet Systems

Tsarist Engineer-Builders: Construction as Imperial Will

Era: 18th – early 20th century

Construction under the Tsars was an act of state power. Projects were initiated by the monarch, financed by the treasury, and executed through coerced labour.

Key Figure (Builder-Architect Hybrid): Auguste de Montferrand (1786–1858)

- Builder and architect of St. Isaac’s Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, a masterpiece of Neoclassical architecture

- Managed thousands of serfs and craftsmen, orchestrating large-scale operations with precision

- Innovated deep foundation engineering to build on swampy terrain, overcoming major geological challenges

- Sourced rare stones such as malachite and granite from across the vast Russian empire

System Profile: Builders like Montferrand were foreign experts or state-appointed engineers with near-unlimited authority, operating in a command environment long before socialism formalised such structures.

The Soviet Stroyka and the Five-Year Plan

Era: 1920s – 1991

Construction became a state function, not an industry. Projects were commanded into existence by the State Planning Committee (Gosplan) and executed by ministries, state-owned trusts, and military construction units.

Labor Sources:

- Paid workers

- Komsomol volunteers

- Gulag prisoners on brutal projects like the Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) railway and Arctic installations

System Outcome: Unmatched scale and speed were achieved at a catastrophic human cost, with uneven construction quality and environmental neglect.

The Proektnye Instituty (Design Institutes)

State design institutes such as Giprogor and TsNIIEP produced standardised drawings for every building type across the USSR.

Impact:

- Enabled mass housing and infrastructure development

- Eliminated individual architectural authorship, producing uniformity

- Created visually monotonous urban landscapes spanning from Prague to Vladivostok

Post-Soviet and Contemporary Builders

STROYGAZMONTAZH (SGM Group)

Founder: Arkady Rotenberg

Specialisation: Pipelines, mega-infrastructure

Key Projects:

- Power of Siberia gas pipeline

- Kerch Strait (Crimean) Bridge

- Sochi Olympics venues

Profile: The archetypal state-corporate builder: privately owned but fully dependent on political patronage and state contracts, often awarded without open tender.

Mosinzhproekt

Moscow’s vertically integrated metro and infrastructure builder since the 1950s. A municipal successor to Soviet mega-trusts, it controls design, construction, and delivery, continuing the tradition of centralised infrastructure development.

Renaissance Construction

A private, internationally oriented contractor operating across Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Its business model more closely aligns with Western general contractors but remains embedded within Russia’s political landscape.

The Panelka Builders and DSK Combines

Factory-like house-building combines mass-produced prefabricated concrete housing blocks that define much of the region’s urban fabric.

Current Challenge: These ageing housing stocks face large-scale retrofitting and thermal modernisation to improve energy efficiency and livability.

From Absolute Authority to Image Production: The Architects of Russia and Eastern Europe

Unlike builders, architects in this region have experienced cycles of total power, total anonymity, and formal freedom without execution control. Here are some of the most influential figures across eras, illustrating the shifting role of architects:

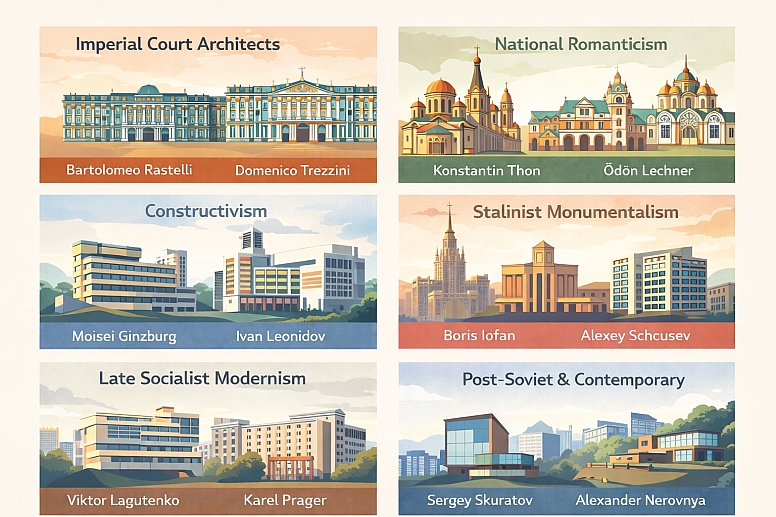

1. Imperial Court Architects (18th – early 19th century)

Bartolomeo Rastrelli (1700–1771)

- Italian-born architect responsible for the exuberant Baroque style of the Russian court

- Designed the Winter Palace and Smolny Cathedral, symbols of imperial wealth and power

- Architecture served as spectacle, reinforcing the hierarchy and grandeur of the monarchy.

Domenico Trezzini (1670–1734)

- Swiss architect and urban planner, chief architect of early St. Petersburg

- Introduced rational street grids and European urban planning principles

- Architecture functioned as a tool for state modernisation and westernisation

Architect Profile: These architects operated as court servants with extraordinary authority, backed by absolute power and the coerced labour of thousands.

2. Late Imperial & National Romanticism (19th century)

Konstantin Thon (1794–1881)

- Official architect of the Russian Empire who codified the “Russian-Byzantine” style

- Designed the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, a nationalist and religious monument

- His style reinforced state-approved nationalism and imperial ideology

Ödön Lechner (1845–1914)

- Hungarian architect, founder of Hungarian Art Nouveau

- Integrated folk motifs into imperial-era buildings to assert national identity

- Worked within multinational empires to give expression to ethnic and cultural distinctiveness

3. Revolutionary Avant-Garde / Constructivism (1917–1932)

Moisei Ginzburg (1892–1946)

- Leading figure of Soviet Constructivism

- Designed the Narkomfin Building, a prototype for communal living and collective housing

- Sought to reshape social relations through radical architectural innovation

Ivan Leonidov (1902–1959)

- Visionary architect of radical, unbuilt megastructures

- Proposed libraries, cultural centres, and urban plans as ideological machines

- His utopian designs symbolised the brief period when architects influenced ideology rather than executed it

4. Stalinist Monumentalism (1933–1955)

Boris Iofan (1891–1976)

- Architect of the grandiose but never-built Palace of the Soviets

- Designed the House on the Embankment, a symbol of Stalinist power

- His architecture embodied theatrical power and state symbolism

Alexey Shchusev (1873–1949)

- Designed the Lenin Mausoleum, balancing symbolism with architectural restraint

- One of the few architects to navigate Stalinist mandates successfully

5. Late Socialist Modernism (1955–1980s)

Viktor Lagutenko

- Architect of Khrushchyovka housing systems, focusing on efficiency and mass housing solutions

- Produced minimalistic architecture driven by economic constraints

Karel Prager (1923–2001)

- Czech architect known for Brutalist civic buildings

- Worked within bureaucratic limits, expressing civic identity in austere forms

Architect Profile: Architects during this period were civil servants in design institutes, judged primarily by productivity rather than creativity.

6. Post-Soviet & Contemporary Era (1990s–present)

Sergey Skuratov

- Prominent Moscow architect engaging with urban development projects

- Navigates tensions between capital interests, regulation, and architectural form

Alexander Brodsky

- Known for “paper architecture” and poetic minimalism

- Emphasises architecture as a cultural reflection rather than mass infrastructure

Alexander Nerovnya

- Specialises in high-end conceptual architecture and visualisation

- Operates globally as an image-maker, highlighting architecture as media and branding

- Represents the shift from architect as system-builder to architect as cultural symbol

Key Shift: Architecture today functions more as content—media, branding, and aspiration—rather than the infrastructural backbone it once was.

Systemic Constraints and Cultural Patterns

- Separation of design and construction authority

- Persistence of monumentalism and architectural isolation

- Informal networks (tychelovek) often override formal processes

- Legacy of Soviet GOST standards impacting modern practice

- Heavy dependence on migrant labour from Central Asia

- Construction as an instrument of political strategy, both domestically and abroad

Two Traditions, One Landscape

Russian and Eastern European construction history is defined by builders who command systems and architects who reflect power—rarely the same people, and rarely equal partners.

- Builders shaped territory, infrastructure, and geopolitics

- Architects shaped symbolism, ideology, and global perception

From imperial absolutism to Soviet standardisation and post-Soviet fragmentation, the region moved from architecture as command to architecture as content—lighter, freer, but detached from the machinery that once built entire cities at once.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who built the Moscow Metro?

The initial metro lines were built under Lazar Kaganovich’s direction, with engineers like Pavel Rottert overseeing construction. Mosinzhproekt remains the primary entity responsible for Moscow’s metro development. The project combined enthusiastic Komsomol volunteers and, later, forced labour, producing iconic, ornate stations known as “palaces for the people.”

What is a Khrushchyovka?

Khrushchyovkas are five-story, prefabricated concrete apartment buildings produced from the late 1950s to the 1980s. Named after Nikita Khrushchev, they addressed acute housing shortages quickly and cheaply. Though once widespread, these buildings are now criticised for poor insulation, small living spaces, and ageing infrastructure. Many Russian cities are actively replacing them.

How did construction change after the Soviet Union collapsed?

The collapse dissolved the state command system. State-owned trusts were privatised, often to their former directors. A new class of politically connected private contractors emerged. Funding shifted to private investment, loans, and oil revenues. While some project quality and variety improved, infrastructure maintenance overall suffered.

What role does Central Asian migrant labour play?

Migrant workers from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan are vital to the Russian construction labour force, especially in Moscow and other major cities. They often work for low wages under difficult conditions and send remittances home. The industry depends heavily on this workforce, managed through quota and permit systems.

Which company built the Kerch Strait Bridge?

The Kerch Strait Bridge was constructed primarily by STROYGAZMONTAZH (SGM), owned by Arkady Rotenberg. Though managed by a federal agency, SGM and its subcontractors executed the project, which was presented as a symbol of national reunification with Crimea and completed on an expedited timeline.

Are there major Russian construction firms active internationally?

Russian firms mainly operate within the former Soviet sphere and allied states, such as countries in the CIS, Serbia, Syria, and some African nations. Renaissance Construction is a notable player in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Unlike Western or Chinese giants, Russian firms have limited global reach due to sanctions, technological constraints, and financing.